I’m a wildlife biologist by day. My work focuses primarily on the ecology of large mammals. I started in the Lake Superior basin, in the land of ridiculous snow. I did my master’s work on the foraging ecology of moose on Isle Royale National Park, and my PhD on winter ecology of white-tailed deer (a VERY diverse topic!).

Here I am in a hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) forest- it's the coolest tree east of the Mississippi. Yes, that's the namesake of my business.

A continued thread through my graduate work was, “What do herbivores eat and why?” For a deer or moose in a Michigan winter, sometimes their food choices are the best of a bad choice (the highest energy winter foods, conifers, often have a lot of plant defensive compounds, which burn a lot of energy to metabolize. That’s a problem if you’re living in a northern climate with very little food available.

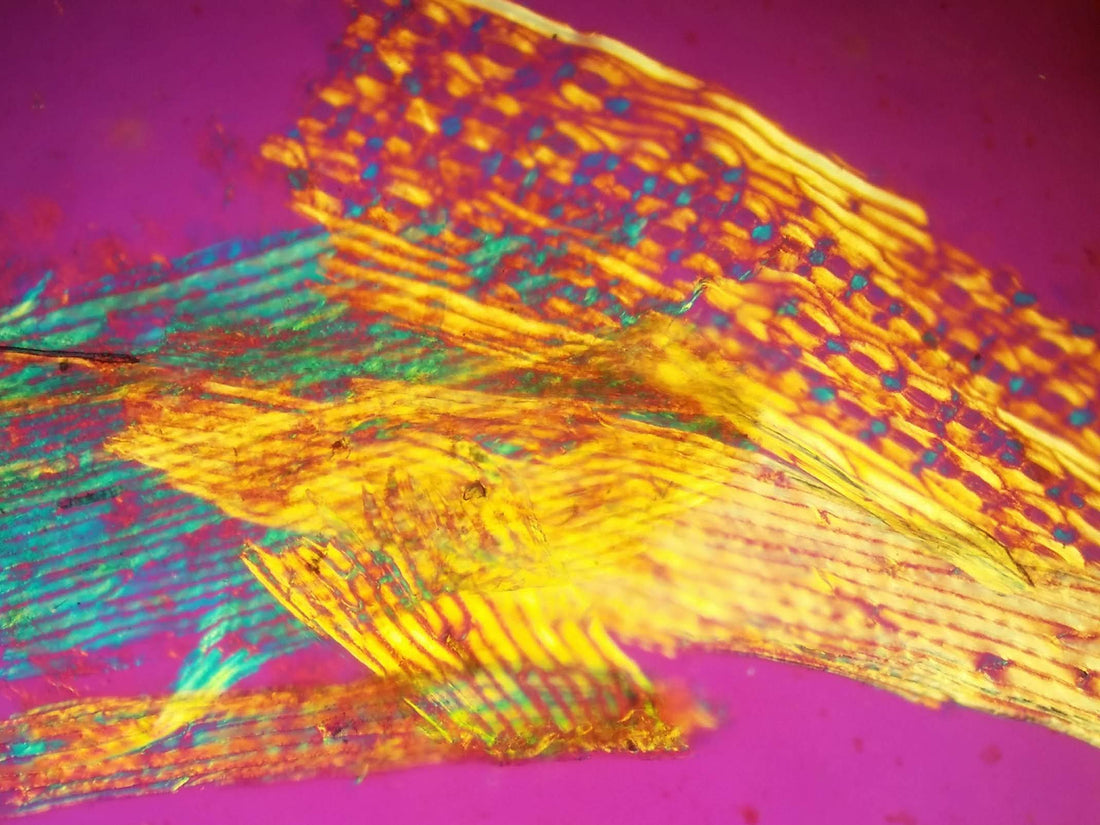

So how do I determine what a moose or deer ate? Poop! Yep! I look at fecal samples under a microscope and I’m able to identify plant species based on cell structure. Here we have an eastern hemlock fragment on the left, and a Canada yew fragment on the right.

We get the fun colors from polarized light microscopy. Here’s a white pine fragment under a standard bright-field microscope (that you might use in a biology class) versus a polarized light microscope. Cool, eh?

I’ve been designing jewelry since high school, and I’ve always loved intricate beadwork. My designs have evolved, but in my 20s, I developed a fascination with lapidary. I was living in the Lake Superior basin at the time, where striking agates are everywhere, and agate hunting is a popular pastime. I flirted with wire-wrapping but couldn’t quite master it. Over the years, I let it percolate- how do I combine my love of intricate beadwork with gemstones? I dabbled in some focal gemstone beads, but the double-drilled gemstone beads were a game-changer! And working behind the microscope as a beader was great. I was comfortable with tiny things that require a lot of patience!

Jewelry design and science have a deceptive amount in common. Specifically, both fields involve genuine curiosity. As a scientist, I craft a hypothesis and investigate it as appropriate. In some cases, the outcome is what I expect. In other cases, there’s a bit more nuance, or the outcome might be totally out of left field! But the latter case is often even more interesting, since you realize that the world is a lot more complicated (and a lot cooler) than you think! Similar to jewelry design- in some cases, I’ll sketch out a design idea, and it goes about as expected. In other cases, I assemble a piece and it’s a total flop- the components sit weird, or they just don’t work together as expected (so we’re doing a little geometry and physics here, too!). In that case, sometimes I let it percolate on my bead table, and in other cases, I’ll look at it, “OK- looks like this particular stitch is causing the peculiar drape of this piece. In some cases, this warrants a total rebuild, like in the case of the Meridian Mesh bracelet.

I tried making these hexagonal bead pendants, but as you can see, they didn’t quite sit right. So, I took apart the whole thing and reimagined the pendants.

Success!

One of my favorite designs, the Stonecrossing bracelet started out like this. I thought that the triangular lattice would stand alone, but nope. It flared out with a spiky look and didn’t look polished.

I added a strand of beads on each end, accented with lilac-colored glass teardrops, and voila!

I’ve found that art and science have a strong synergy. In both cases, there’s a bit of experimentation and hypotheses involved. But scientists also benefit from having a creative side. We scientists are always coming up with new ways to display our data that tell a story better than a block of text.

My PhD advisor was the king of such graphs. Every time we met, he’d find a random piece of paper and say, “Hey- I found this cool graph in a journal. We should try this with your data.” And he’d sketch it in chicken scratch. I’d experiment with it. In some cases, my data would work really well with a particular graph, and in other cases, it would look like a Jackson Pollock painting. So back to the drawing board. So having visual creativity is beneficial as a scientist.

Not to mention, once I get into the flow of a particular design, it’s almost meditative and helps clear my head after doing data analysis or field work.

I’m very thankful that I’ve been able to nurture passions for both science and art!